Our gardens continue to bloom and produce food. While they do, here is a haibun series in celebration. It’s from my Pecan Grove Press book The Local Cluster. As always, the way to receive this book tax and postage free is directly from the poet: colinmorton550@gmail.com $15.

Hortus Urbanus / City Garden

Twice now this morning I am wakened by full-throated geese Veeing over my roof. How is a poet to dream through this?

High in the wind-torn pine a cardinal pipes his claim to all he surveys. From chimney top the crow replies sharply. In cedar branches sparrows watch a blue jay splash in the water.

Fleet light, how do you

taste? How have you left no tracks

in reaching this place?

~

I pay in silver for bags of earth to level the ground round the roots of a thirsty shade tree deep in the intricate heart of a city at the confluence of three rivers where once was forest and swamp.

The scene calls for Kurosawa’s camera and patience, for a narrator if you must: a wolf. Or the spirit of a wolf, who once would have kept down the raccoons who rattle my garbage cans at night. One who stares back, unafraid of my bluff.

Bats in the branches. O, and the moon is full. Already, I think, then remember how long it must be since I looked up at night and caught in the corner of my eye a fleeting wing.

A sound in the garden

— fallen branch or door slammed —

then silence recomposing around it.

~

In this garden, maple is a weed. It infiltrates from melting snow like stick insects about to take wing. Then the yellow parachutes descend, and soon whirlybirds everywhere, scattering.

In the splash line under the eaves, out of street sweepings, in the crack between pavement and foundation, the maple keys grow. Sometimes a sapling wedged between rocks against the fence reaches shoulder height before I find and uproot it.

It’s a game of stealth. Given time and neglect it would bring my house down. I bend and tug.

I know this isn’t nature, or

I would live in a grove not an avenue.

My life’s as forced as a hybrid rose.

~

Don’t suppose the garden’s a silent refuge. In the ice storm, a tree fell across the street and for two weeks no buses ran. No rush hour. All but rescue crews stayed home. Then silence encased the city, shattered only by falling ice, the moan of tree trunks bent low.

With fine weather construction crews return. They clear debris, knock down walls, drive fenceposts, dig foundations. The ball-capped wood-tappers emerge from their dwellings with power saws. Then there’s the sawing of mosquitoes.

This isn’t what the magazine headlines mean bythe poetry of the garden. If you want to escape the grind, the neighbours’ deck at semester’s end with canvas chairs, radio and a cooler full of beer serves as well and better.

Down here in the dirt, it’s real

dung beetle country:

the greatest shit of all time

without commercial interruption.

~

With a fork like this my grandfather stacked five hundred bails before noon, then sat on the last and open his Thermos, ate sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, and counted his herd’s winter feed against next spring’s likely price for beef on the hoof. In an hour my hands blister, turning compost rank with corruption, which next summer will midwife sweet drafts of lilac, peony, lily on the breeze.

What chemistry! with Whitman I exult. That the winds are not really infectious … That the cool drink from the well tastes so good. Yet I filter my water again, through charcoal, as I moderate my vices, read labels as if avoiding what kills will save me.

Over the slimy stew of roots and leaves I spread ash from the fire, bone meal, dry stalks, dead-headed flowers. Death’s dominion’s reduced to this little black box, the size of the Arc of the Covenant.

From nothing: this!

From something destroyed: this!

and this! and this!

~

Here before Noah lay strata of ice.

Then for a thousand years, sea bottom. Till glacial runoff carried down a moraine that trapped a freshwater lake. Which turned back to ocean a thousand years later when the tide broke through again, finally retreating as, unburdened of ice, the porous land rose.

Beneath my spade I discover trilobites and bottle caps, no shards or arrowheads, more crushed rock than soil.

The wing of the bee

in its figure-eight beat: O

lead me to the goods.

~

With bleach and brush I scrub algae from the lime-rich bottom of the birth bath. I drain and rinse, then refill for the neighbourhood sparrows and chickadees who gather at the gushing sound. And for the blue jay, who loudly announces his arrival, pauses on an overhanging branch and then, unchallenged, drops to the laurel-wreathed concrete rim. Ostentatiously he sips, sips again, then wades in till his long blue tailfeathers drip. Here he squats and beats his wings, spraying the ground beneath.

There follow the dodgier finches that approach in small, skittish steps, aborted landings. Sparrows skim in low to the ground, sans scruples over drinking another’s bath water.

Soon I will have to scrub again, drain the fertile water over parched lilies, drooping peonies and sprawling poppies—the overabundance that reigns so briefly after months of desert grey and struggling bud. Now rather than feed and coax must the gardener split and spread new growth, swap or bequest or abandon the unstoppable violets.

A small pool contains

— like an open eye —

the world and all.

~

On his northern journey, haiku master Basho saw the split-trunk pine of Takekuma celebrated in ancient verse, though of its fall into the river, too, he knew from not-quite-so-ancient verse.

Many times fallen and replanted, the tree always grew with a split, like the first, thanks to a slip of the woodsman’s ax.

For myself, I undertake no pilgrimage but remain year after year under the same white pine. Wind-riven, spare and lean, a tree of the northern wild with roots twisting deep into limestone beneath a handful of earth.

A few brush strokes on vellum:

craggy historian, lone

pine bent by the wind.

~

Whatever mulching or moving of earth we yesterday left undone may remain now in whatever state we left it until spring. The birdbath’s concrete laurel leaves hold a loaf of snow that will rise and fall with winter’s storms and thaws.

Squirrels chase each other through the cedar, scrap over a cache of food high in the branches of the birch.

One fall day, after digging stones from the garden soil, I set two on end, another across them like Stonehenge, a limestone wedge on top: a mannikin’s head, inukshuk, Herm, a pet who needs no care, who stands out in the windswept snow whenever I look from the window.

Dried flower heads above the snow

— crow and chickadee

eye each other silently.

~

Wintering over: bulbs in deep slumber; roots’ icy nooses; snug branches under yellowed leaves, heaped up around the rose, whose thorny canes slowly mulch them in the drying wind.

Green tendrils hang around the double-glazed window. Steam writhes against the cold pane, turns back on itself like bonsai, barely rising from the teapot’s spout.

On the table beside the tray: the open pages of a glossy garden magazine, a chewed pencil stub, the order form torn from a seed catalogue.

Rose red setting sun

skates the horizon southward.

The windowsill cat

flexes her claws in a dream.

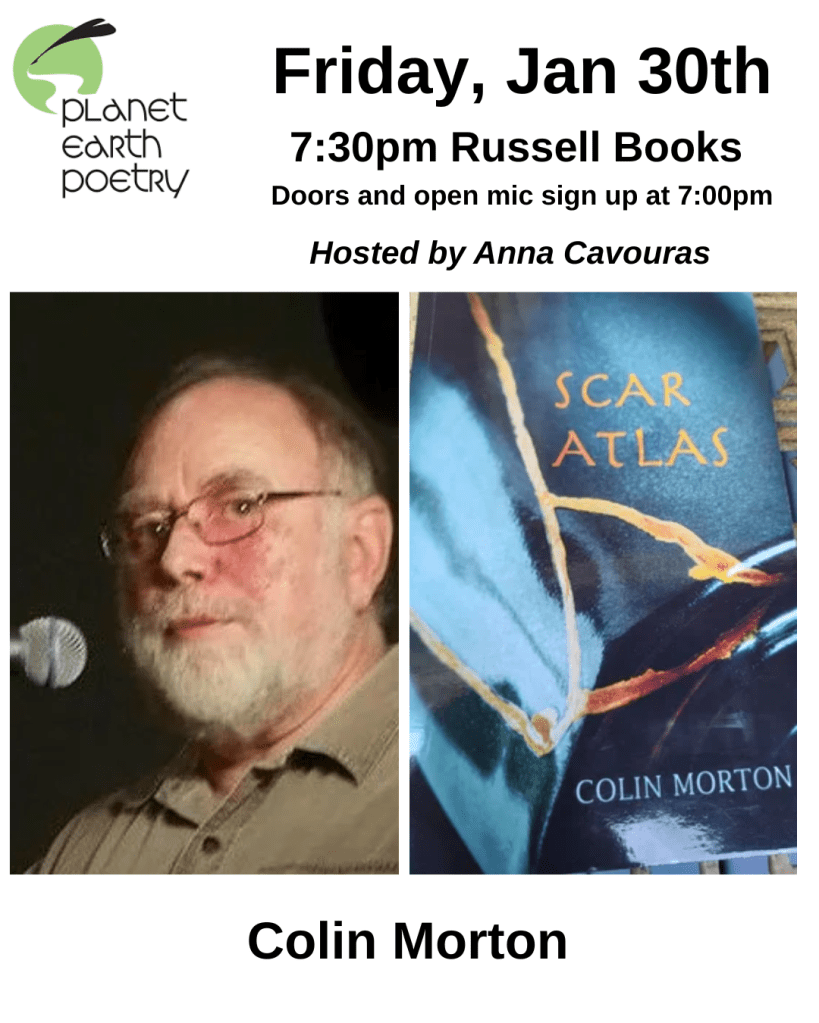

Colin Morton’s 2024 book Scar Atlas is one of ten books by established Canadian poets long-listed for the prestigious Al and Eurithe Purdy award. The $10,000 prize winner will be announced in April, so you have time to read them all. One way to receive Scar Atlas by mail is to email me directly at colinmorton550@gmail.com. The ten books in contention for the prize are:

Read more about the Purdy award at Quill and Quire: https://quillandquire.com/omni/al-eurithe-purdy-poetry-prize-longlist-for-2025-announced/

You can also find a review of Scar Atlas in Devour magazine online.

Two excellent Canadian literary magazines found room for my work on their pages this winter.

I recommend you check them out, and to get an idea of the kind of work they print, you could start by reading my poems here.

Prism international, based in Vancouver, includes my “Tinnitus” in its new issue:

Tinnitus

I read John Cage and, in a silent room,

listened to the low thrum of blood in my veins,

the hiss of nerves in my head.

Proprioception I called it, after Olson.

For years I believed what I heard

was the microbiome of my inner ear –

cells living out their lives in there –

and I wondered about this thing called me.

How much of me is a population

of microbes doing I don’t know what

to or for me, living and dying

as I say these words?

Now I accent the first syllable,

call it tinnitus, as if that’s an explanation.

I told the doctor, I guess there’s little I can do.

You can complain, he said.

Waterloo, Ontario magazine The New Quarterly includes two of my poems, and I have written a blog post about one of them for the TNQ blog. Here are the poems.

Dark Flower

What fresh hellebore is this that flowers

deep purple, deeper than its shallow

sunny fellows?

How deep

to flower in winter, face frost

and snow, to know when to bow,

how not to break.

Burgundy bloom,

have you a tincture for me and my fellows?

A word to the wayward perhaps?

Or a charm to scare the devil

out of any who cross us?

Would you at least come live with me

and be my dark midwinter comfort?

Please forgive my forwardness.

You are, and that’s enough for me.

Nocturne

Wind in the branches

Whispering waves

How much of our poetry is

staging

the abalone bed for

a single small pearl

found on a petal

or a rainy street

on the crest of a breaker

in the beak of a raptor

in the depths of the sea

or the eye socket of a skull

If you could see its gleam

without the setting

you’d be left without

a poem to learn

It would turn in your mind

like a moon

We’ve been away from the computer a lot this summer, but have been keeping up appearances online, with poems at these wonderful web zines:

In the U.S., Ascent published my “Crepuscule” many years after editor Scott Olsen asked to talk about aging.

Valparaiso Poetry Review reached back millions of years with my poem “Footprints.”

In Canada, the new Juniper Review allowed me to give a birthday gift to my wife Mary Lee Bragg with the poem “Amnesia.”

Not incidentally, Mary Lee Bragg has just published her first full poetry collection, The Landscape that Isn’t There, from Aeolus House Press. It is the mature work of a lifetime, as you know if you heard her read at the Aeolus House launches in Toronto and Ottawa recently. She will be giving readings from the book in Ottawa at Tree in October and in Victoria at Planet Earth in January.

So we’re quiet here, and spend much of every day in silence, but all along, things are humming.

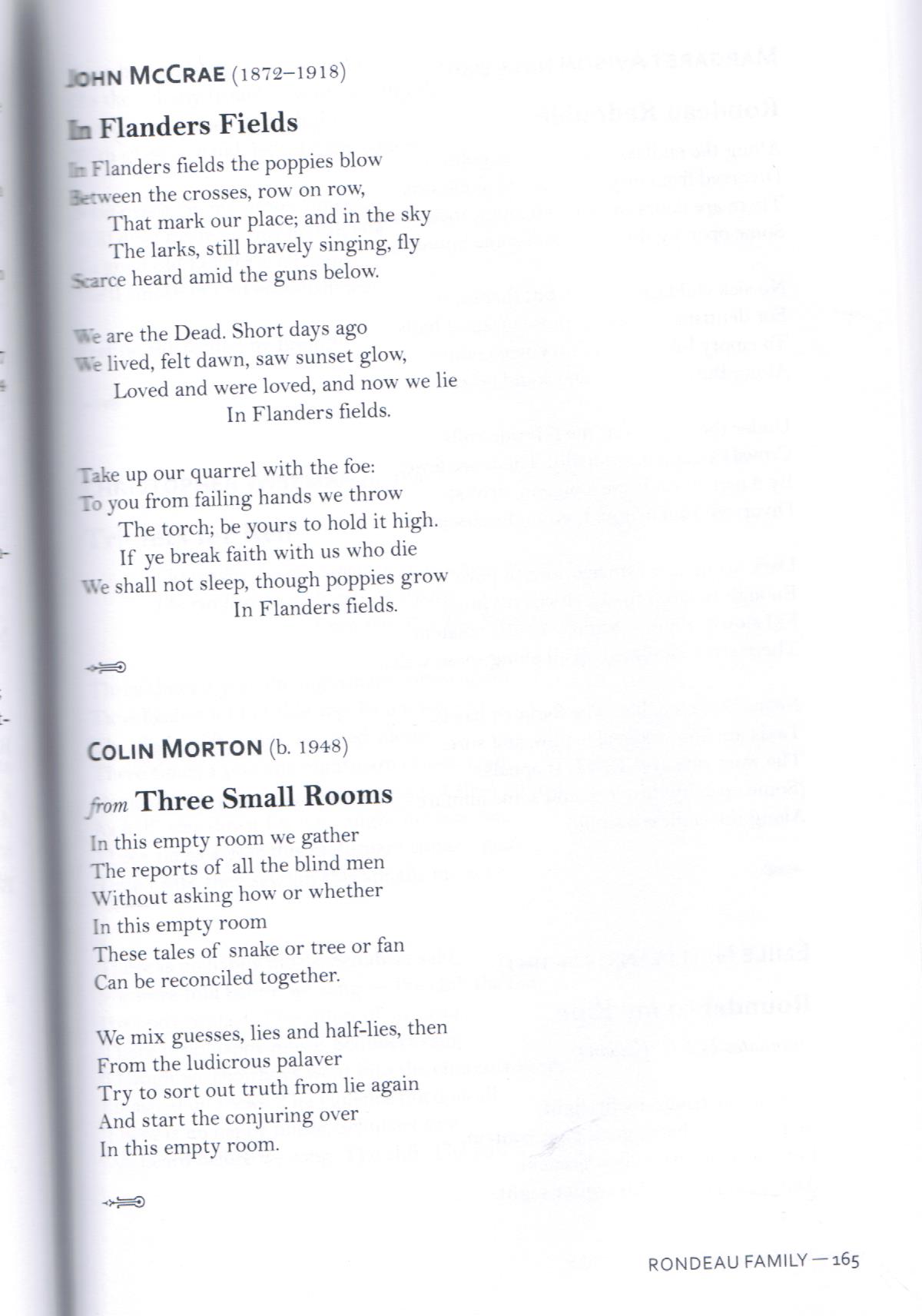

My bionote in an issue of Grain magazine dating back to 1979 said my goal was to write in every poetic form, “sonnet, sestina, serial poem” and also the ones that don’t start with s. Four decades later, while I like to think I’m still in mid-career, I see that I have at least tried my hand at nearly every form categorized in the extra-fine new second edition of the anthology In Fine Form, edited by Kate Braid and Sandy Shreve. Their selection, from two hundred years of Canadian poetry, covers the landscape encyclopedia style: Ballad; Blues; Epigram; Found Poems; Fugue and Madrigal; Ghazal; Glosa; Haiku and Other Japanese Forms; Incantation; Lipogram; Palindrome; Pantoum; Pas de Deux; Prose Poem; Rondeau Family; Sestina; Sonnet; Spoken Word; Stanzas; Villanelle; each gets a chapter … And More. The editors take troubles to introduce the forms, many of them ancient, and review how they’ve developed under the pens and keyboards of today’s poets. Examples follow, ordered not chronologically but according to how closely the poet has followed the models, progressing toward more and more experimental interpretations.

My bionote in an issue of Grain magazine dating back to 1979 said my goal was to write in every poetic form, “sonnet, sestina, serial poem” and also the ones that don’t start with s. Four decades later, while I like to think I’m still in mid-career, I see that I have at least tried my hand at nearly every form categorized in the extra-fine new second edition of the anthology In Fine Form, edited by Kate Braid and Sandy Shreve. Their selection, from two hundred years of Canadian poetry, covers the landscape encyclopedia style: Ballad; Blues; Epigram; Found Poems; Fugue and Madrigal; Ghazal; Glosa; Haiku and Other Japanese Forms; Incantation; Lipogram; Palindrome; Pantoum; Pas de Deux; Prose Poem; Rondeau Family; Sestina; Sonnet; Spoken Word; Stanzas; Villanelle; each gets a chapter … And More. The editors take troubles to introduce the forms, many of them ancient, and review how they’ve developed under the pens and keyboards of today’s poets. Examples follow, ordered not chronologically but according to how closely the poet has followed the models, progressing toward more and more experimental interpretations.

Saturday, Feb. 6, 7:30 at Ottawa’s Carlton Tavern, several contributors to rob mclennan’s annual poetic and artistic showcase of national capital-related talent, http://www.ottawater.com/

I’ll be among the readers. Ottawater’s always-elegant design isn’t quite ready yet, but a whole decades’ archive of previous volumes can still be read at the site.