Our gardens continue to bloom and produce food. While they do, here is a haibun series in celebration. It’s from my Pecan Grove Press book The Local Cluster. As always, the way to receive this book tax and postage free is directly from the poet: colinmorton550@gmail.com $15.

Hortus Urbanus / City Garden

Twice now this morning I am wakened by full-throated geese Veeing over my roof. How is a poet to dream through this?

High in the wind-torn pine a cardinal pipes his claim to all he surveys. From chimney top the crow replies sharply. In cedar branches sparrows watch a blue jay splash in the water.

Fleet light, how do you

taste? How have you left no tracks

in reaching this place?

~

I pay in silver for bags of earth to level the ground round the roots of a thirsty shade tree deep in the intricate heart of a city at the confluence of three rivers where once was forest and swamp.

The scene calls for Kurosawa’s camera and patience, for a narrator if you must: a wolf. Or the spirit of a wolf, who once would have kept down the raccoons who rattle my garbage cans at night. One who stares back, unafraid of my bluff.

Bats in the branches. O, and the moon is full. Already, I think, then remember how long it must be since I looked up at night and caught in the corner of my eye a fleeting wing.

A sound in the garden

— fallen branch or door slammed —

then silence recomposing around it.

~

In this garden, maple is a weed. It infiltrates from melting snow like stick insects about to take wing. Then the yellow parachutes descend, and soon whirlybirds everywhere, scattering.

In the splash line under the eaves, out of street sweepings, in the crack between pavement and foundation, the maple keys grow. Sometimes a sapling wedged between rocks against the fence reaches shoulder height before I find and uproot it.

It’s a game of stealth. Given time and neglect it would bring my house down. I bend and tug.

I know this isn’t nature, or

I would live in a grove not an avenue.

My life’s as forced as a hybrid rose.

~

Don’t suppose the garden’s a silent refuge. In the ice storm, a tree fell across the street and for two weeks no buses ran. No rush hour. All but rescue crews stayed home. Then silence encased the city, shattered only by falling ice, the moan of tree trunks bent low.

With fine weather construction crews return. They clear debris, knock down walls, drive fenceposts, dig foundations. The ball-capped wood-tappers emerge from their dwellings with power saws. Then there’s the sawing of mosquitoes.

This isn’t what the magazine headlines mean bythe poetry of the garden. If you want to escape the grind, the neighbours’ deck at semester’s end with canvas chairs, radio and a cooler full of beer serves as well and better.

Down here in the dirt, it’s real

dung beetle country:

the greatest shit of all time

without commercial interruption.

~

With a fork like this my grandfather stacked five hundred bails before noon, then sat on the last and open his Thermos, ate sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, and counted his herd’s winter feed against next spring’s likely price for beef on the hoof. In an hour my hands blister, turning compost rank with corruption, which next summer will midwife sweet drafts of lilac, peony, lily on the breeze.

What chemistry! with Whitman I exult. That the winds are not really infectious … That the cool drink from the well tastes so good. Yet I filter my water again, through charcoal, as I moderate my vices, read labels as if avoiding what kills will save me.

Over the slimy stew of roots and leaves I spread ash from the fire, bone meal, dry stalks, dead-headed flowers. Death’s dominion’s reduced to this little black box, the size of the Arc of the Covenant.

From nothing: this!

From something destroyed: this!

and this! and this!

~

Here before Noah lay strata of ice.

Then for a thousand years, sea bottom. Till glacial runoff carried down a moraine that trapped a freshwater lake. Which turned back to ocean a thousand years later when the tide broke through again, finally retreating as, unburdened of ice, the porous land rose.

Beneath my spade I discover trilobites and bottle caps, no shards or arrowheads, more crushed rock than soil.

The wing of the bee

in its figure-eight beat: O

lead me to the goods.

~

With bleach and brush I scrub algae from the lime-rich bottom of the birth bath. I drain and rinse, then refill for the neighbourhood sparrows and chickadees who gather at the gushing sound. And for the blue jay, who loudly announces his arrival, pauses on an overhanging branch and then, unchallenged, drops to the laurel-wreathed concrete rim. Ostentatiously he sips, sips again, then wades in till his long blue tailfeathers drip. Here he squats and beats his wings, spraying the ground beneath.

There follow the dodgier finches that approach in small, skittish steps, aborted landings. Sparrows skim in low to the ground, sans scruples over drinking another’s bath water.

Soon I will have to scrub again, drain the fertile water over parched lilies, drooping peonies and sprawling poppies—the overabundance that reigns so briefly after months of desert grey and struggling bud. Now rather than feed and coax must the gardener split and spread new growth, swap or bequest or abandon the unstoppable violets.

A small pool contains

— like an open eye —

the world and all.

~

On his northern journey, haiku master Basho saw the split-trunk pine of Takekuma celebrated in ancient verse, though of its fall into the river, too, he knew from not-quite-so-ancient verse.

Many times fallen and replanted, the tree always grew with a split, like the first, thanks to a slip of the woodsman’s ax.

For myself, I undertake no pilgrimage but remain year after year under the same white pine. Wind-riven, spare and lean, a tree of the northern wild with roots twisting deep into limestone beneath a handful of earth.

A few brush strokes on vellum:

craggy historian, lone

pine bent by the wind.

~

Whatever mulching or moving of earth we yesterday left undone may remain now in whatever state we left it until spring. The birdbath’s concrete laurel leaves hold a loaf of snow that will rise and fall with winter’s storms and thaws.

Squirrels chase each other through the cedar, scrap over a cache of food high in the branches of the birch.

One fall day, after digging stones from the garden soil, I set two on end, another across them like Stonehenge, a limestone wedge on top: a mannikin’s head, inukshuk, Herm, a pet who needs no care, who stands out in the windswept snow whenever I look from the window.

Dried flower heads above the snow

— crow and chickadee

eye each other silently.

~

Wintering over: bulbs in deep slumber; roots’ icy nooses; snug branches under yellowed leaves, heaped up around the rose, whose thorny canes slowly mulch them in the drying wind.

Green tendrils hang around the double-glazed window. Steam writhes against the cold pane, turns back on itself like bonsai, barely rising from the teapot’s spout.

On the table beside the tray: the open pages of a glossy garden magazine, a chewed pencil stub, the order form torn from a seed catalogue.

Rose red setting sun

skates the horizon southward.

The windowsill cat

flexes her claws in a dream.

- Colin Morton colinmorton550@gmail.com

grandfather, Elder Squire Morton. An itinerant lay preacher, Squire ranged widely on his twice-yearly missionary trips, between Niagara in the west and Oshawa in the east, and he gave a corner of his farm for the first Methodist (“Christian”) church in his community. His grave marker in Unionville cemetery quotes New Testament scripture about having “fought the good fight” and continues with ever smaller, more cramped and illegible scripture, indicative perhaps of the sermons the elder gave in kitchens, school rooms, and on hillsides “from Sharon north to the lake.”

grandfather, Elder Squire Morton. An itinerant lay preacher, Squire ranged widely on his twice-yearly missionary trips, between Niagara in the west and Oshawa in the east, and he gave a corner of his farm for the first Methodist (“Christian”) church in his community. His grave marker in Unionville cemetery quotes New Testament scripture about having “fought the good fight” and continues with ever smaller, more cramped and illegible scripture, indicative perhaps of the sermons the elder gave in kitchens, school rooms, and on hillsides “from Sharon north to the lake.”

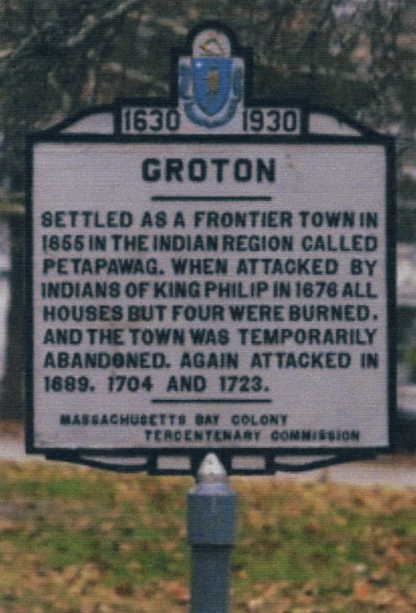

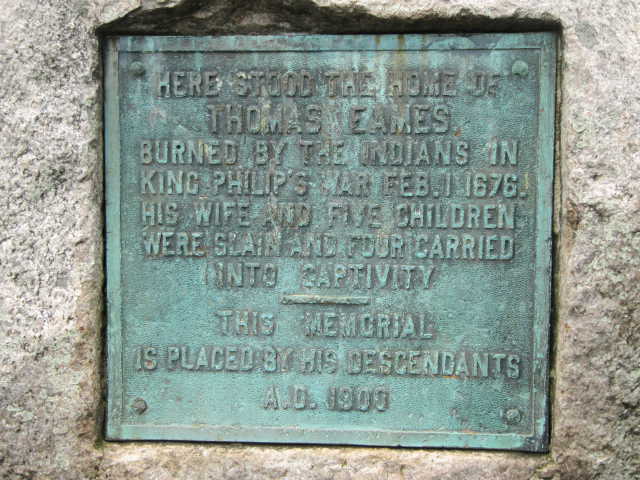

A breaking point came in 1676 with what is known as King Phillip’s War. The war ended terribly for King Phillip, the Wampanoag chief who tried to take back the land he had sold. Many died in the fighting, and more from disease or starvation after being driven out of their villages. The rest were taken in and absorbed by neighboring tribes. English settlers suffered badly too: in proportion in the population, King Phillip’s War was more devastating than the Civil War two centuries later. A third of English towns and villages were destroyed or abandoned, including Groton, Massachusetts, where two of my ancestors (John Nutting and his son John) were killed, and another (Major Simon Willard) led the militia that raised the siege of the town. In the kind of collective punishment that I decried when practised against Sitting Bull’s Lakota in my bo

A breaking point came in 1676 with what is known as King Phillip’s War. The war ended terribly for King Phillip, the Wampanoag chief who tried to take back the land he had sold. Many died in the fighting, and more from disease or starvation after being driven out of their villages. The rest were taken in and absorbed by neighboring tribes. English settlers suffered badly too: in proportion in the population, King Phillip’s War was more devastating than the Civil War two centuries later. A third of English towns and villages were destroyed or abandoned, including Groton, Massachusetts, where two of my ancestors (John Nutting and his son John) were killed, and another (Major Simon Willard) led the militia that raised the siege of the town. In the kind of collective punishment that I decried when practised against Sitting Bull’s Lakota in my bo ok The Hundred Cuts, the Wampanoag and their allies attacked English farms at random, including the home of my ancestor Thomas Eames, who left an itemized account of every lamb, wagon, blanket and sack of corn he lost, beginning with “a wife and nine children.” The compensation awarded him by the colonial government after the war was “200 acres near to Mount Waite,” a fair description of where King Phillip’s home village had been located, the last piece of land he did not sell.

ok The Hundred Cuts, the Wampanoag and their allies attacked English farms at random, including the home of my ancestor Thomas Eames, who left an itemized account of every lamb, wagon, blanket and sack of corn he lost, beginning with “a wife and nine children.” The compensation awarded him by the colonial government after the war was “200 acres near to Mount Waite,” a fair description of where King Phillip’s home village had been located, the last piece of land he did not sell. Here you can find out about poet and writer Colin Morton, read excerpts from his

Here you can find out about poet and writer Colin Morton, read excerpts from his